San Ciriaco

AUGUST 16-18, 1899

Quick Facts

Storm Type | Cat. 3 Hurricane

NC Landfall | Hatteras

NC Wind Speed | 140 mph

NC Storm Surge | no data

NC Rainfall | no data

NC Pressure | 28.55 in

Total Deaths | 3,433

NC Deaths | unknown

Total Cost Then | unknown

Total Cost 2009 | unknown

Source: Monthly Weather Review, August 1899 http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/lib1/nhclib/mwreviews/1899.pdf

ABOUT THE STORM

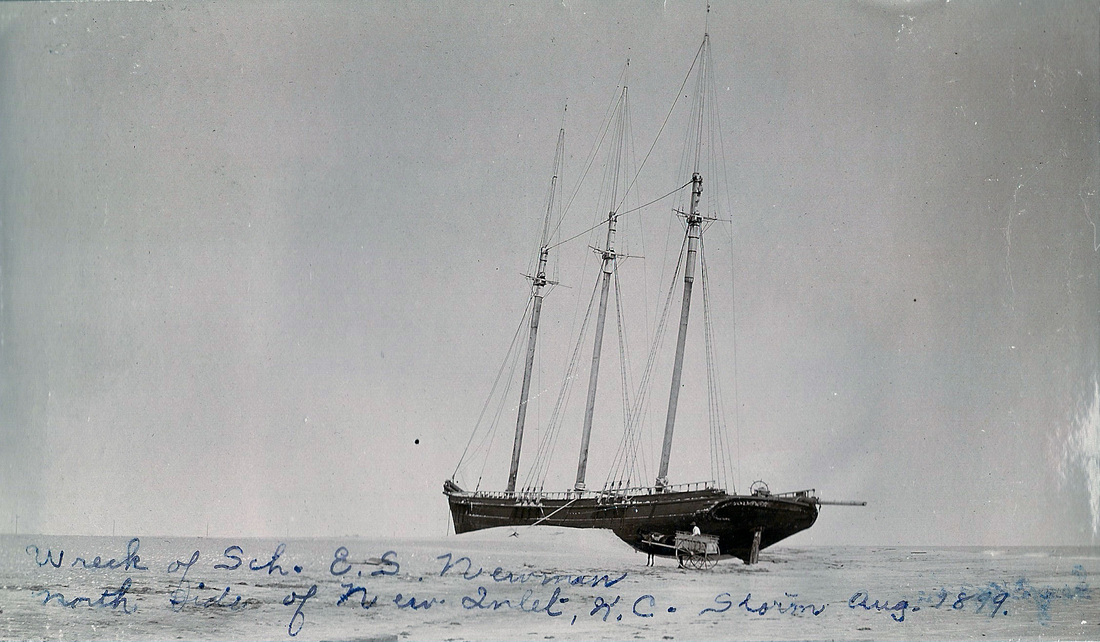

Six years after the 1893 season, North Carolina was again ravaged by two hurricanes in the same year. And once again, these great storms made landfall in August and October. This time, however, both hurricanes made direct hits on the North Carolina coastline: one across the Outer Banks and the other just below Wilmington.

The Great Hurricane of August 1899 was one of the most powerful cyclones to move through the western Atlantic in the nineteenth century. It is often referred to as the San Ciriaco Hurricane, a name given it by the people of Puerto Rico, where it crossed without warning on August 8, killing hundreds. The following day, the hurricane swept over the Dominican Republic and then brushed northern Cuba on the tenth. Its northwestward movement brought it near Florida’s prized oceanfront resorts, and on August 13, the gently curving storm swept past the Fort Lauderdale region. As it followed the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, its continued movement might have carried it east of Cape Hatteras and out of harm’s way. But on the morning of August 16, its forward speed slowed considerably, its direction changed to the northwest, and it increased in strength as it moved toward Cape Lookout.

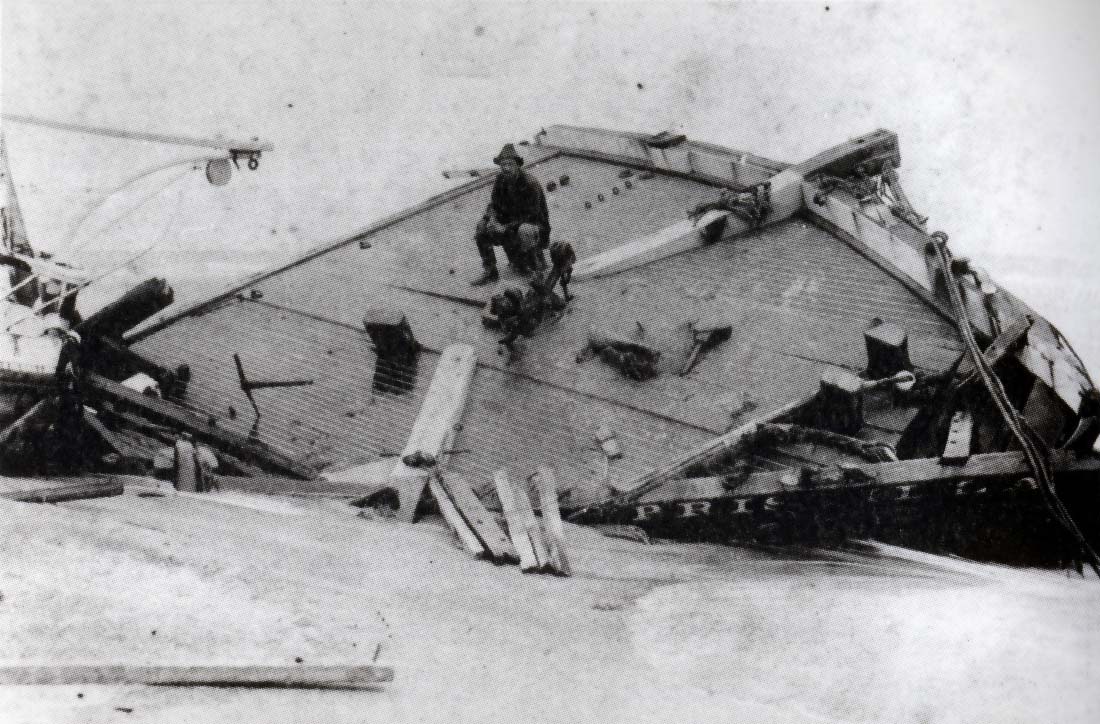

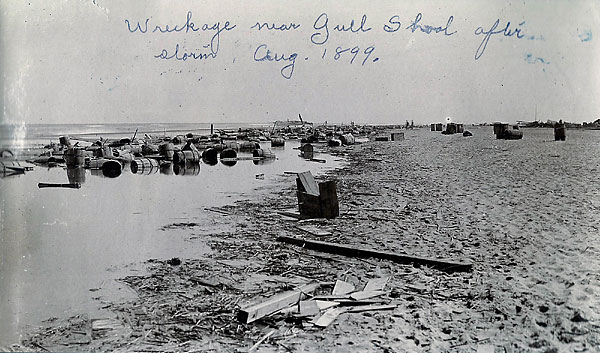

On the morning of August 17, San Ciriaco swept over the lower banks near Diamond City. Reports of great destruction from Beaufort to Nags Head were later printed in newspapers across the country. In Carteret County, the island communities of Shackleford Banks, Diamond City, and Portsmouth were especially hard hit. These fishing villages were settled by hardy families who were accustomed to foul weather and remote lifestyles. But numerous hurricanes and northeasters near the end of the century had tested the endurance of the people known as “Ca’e Bankers.” These storms left drifts of barren sand that replaced the rich soils of their gardens, and saltwater overwash killed trees and contaminated drinking wells. These communities had begun to see a decline in population prior to 1899, largely due to the unwelcome effects of hurricanes.

For the residents of Diamond City and Shackleford Banks, the San Ciriaco Hurricane was the final blow. Few if any of the homes in these island villages escaped the rushing storm tide that swept over the banks. First, the waters rose from the soundside, as northeast winds pounded the islands during the hurricane’s approach. Then, as the storm passed, the winds shifted hard to the southwest, surging the ocean’s tide over the dunes until the waters met. Cows, pigs, and chickens drowned, fishing equipment was destroyed, and many homes were ruined. The aftermath was a truly ghastly scene, as battered caskets and bones lay scattered, unearthed by the hurricane’s menacing storm surge.

Following the San Ciriaco storm, the people of Diamond City and Shackleford Banks gathered their remaining belongings and searched for new places to live. Many moved to the mainland, setting in Marshallberg, Broad Creek, and the Promised Land section of Morehead City. Others moved down to the island of Bogue Banks and became squatters among the dunes of Salter Path. Bust most chose to relocate within sight of their former community, three miles across the sound on Harkers Island. Some even salvaged their island homes, floating them across the water on barges and repositioning them on new foundations.

One of the great tragedies of the hurricane of August 1899 fell upon several families from down-east Carteret County. August was mullet-fishing time, and a large group of men would gather their nets, tents, and provisions for a two-week expedition to Swan Island each summer. Their means of transportation was a small dead-rise skiff, twenty-one feet long and about five feet wide. Each shallow skiff could carry two men and their equipment, and each craft featured a small sail on a removable mast. These shallow-draft boats provided effective transport on the protected waters of Core Sound.

This August, a group of twenty fishermen had already established their camp on the remote island when the first signs of the San Ciriaco Hurricane were recognized. At first, the brisk winds and gathering clouds appeared to be just a good “mullet blow,” which would get the fish moving. But on the morning of August 17, the tide was unusually high, and heavy rains began to sweep through the sound. Alarmed by the rising water, the fishermen considered leaving but chose to stay on the island for fear of the ever-increasing winds. They were forced to pack all of their nets and supplies aboard their skiffs, as the tides washed completely over the island. They moored their skiffs as close together as they could and crouched under their canvas sails for protection from the driving rain. This proved useless, however, as they soon had to bail the water that rapidly filled their boats.

The fishermen worked frantically to keep their skiffs afloat while 100-mph winds churned the waters and tested their anchor lines. For several hours, the courageous men rode out the storm, until finally, in the early hours of August 18, the winds subsided. The tide was now unusually low, as the hurricane’s winds had pushed a surge of water westward up the Neuse River. Battered but still together, the fishermen debated making a run for the mainland, as they could now put up sail. They knew that this journey of less than ten miles would test their skills. Not all agreed to the plan, but after a few had left, the others soon followed. This proved to be a great mistake. The lull that gave them the opportunity to leave was nothing more than the passing of the hurricane’s eye over Swan Island. Within minutes, the storm’s winds were again full force, this time gusting from the southwest. The small skiffs were now out on West Bay, and most were capsized by the wind and waves when a ten-foot surge of water washed back from the Neuse River.

Only six of the twenty men survived. Among those who were rescued were Allen and Almon Hamilton, who saved themselves by quickly taking down their mast and sail, throwing their nets overboard, and lying low in their skiff as it was tossed about. Fourteen others were not as lucky. Of those who drowned, ten were from Sea Level: Joseph and John Lewis, Henry and James Willis, Bart Salter, John Stryon, William Salter, John and Joseph Salter, and Micajah Rose. Four brothers from the community of Stacy were lost: John, Kilby, Elijah, and Wallace Smith.

Ocracoke Island was also hard hit by San Ciriaco. The August 21 edition of the Washington Gazette reported: “The whole island of Ocracoke is a complete wreck as a result of fierce storm which swept the entire coast of North Carolina, leaving ruin and disaster in its path. . . Thirty-three homes were destroyed and two churches were wrecked. Practically every house on the island was damaged to some extent. . . The Barometer went down to 28.3, which is the lowest ever known there and the storm was the most severe ever known to the oldest inhabitants.” The article also reported that waves twenty to thirty feet high pounded the beach and that the hurricane’s storm tide covered the island with four to five feet of water. Hundreds of Banker ponies, sheep, and cows drowned. The dazed survivors of Ocracoke endured “much suffering” after the storm from a lack of food and water.

The residents of Ocracoke and other Outer Banks communities were wise to the effects of rising hurricane tides. Many installed “trap doors” in the floors of their homes to allow rising water to enter, thus preventing the structure from floating off of its foundation and drifting away. Some simply bored holes in the floorboards to relieve the water’s pressure. Occasionally, desperate times called for desperate measures. Big Ike O’Neal described his adventure in the ’99 storm to Associated Press columnist Hal Boyle: “The tides were rising fast and my ole dad, fearful that our house would wash from it foundations, said ‘Here son, take this axe and scuttle the floor.’ I began chopping away and finally knocked a hole in the floor. Like a big fountain the water gushed in and hit the ceiling and on top of the gusher was a mallard duck that had gotten under our house as the tides pushed upwards.”

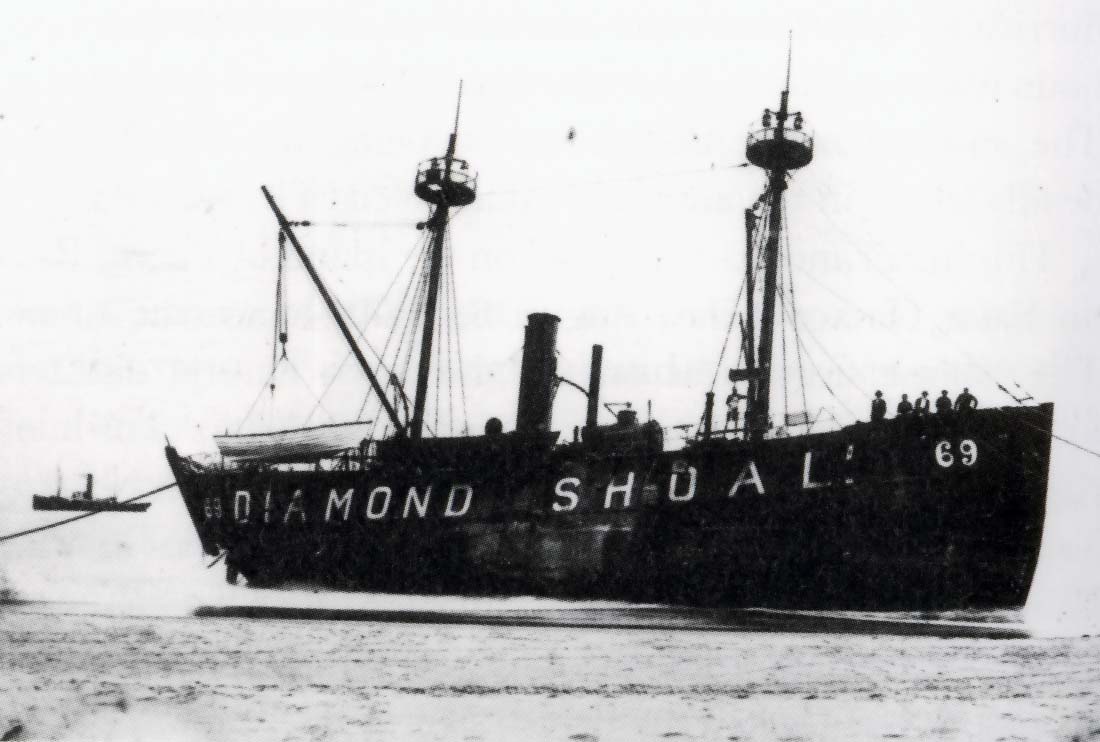

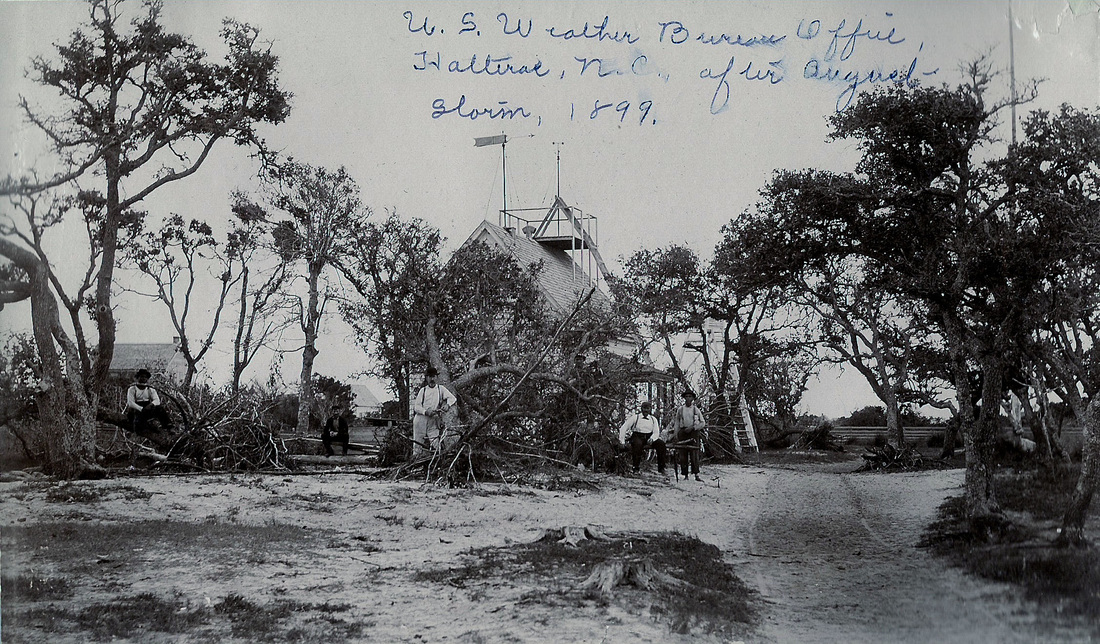

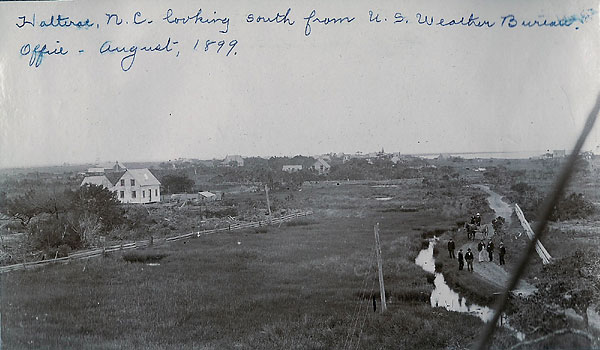

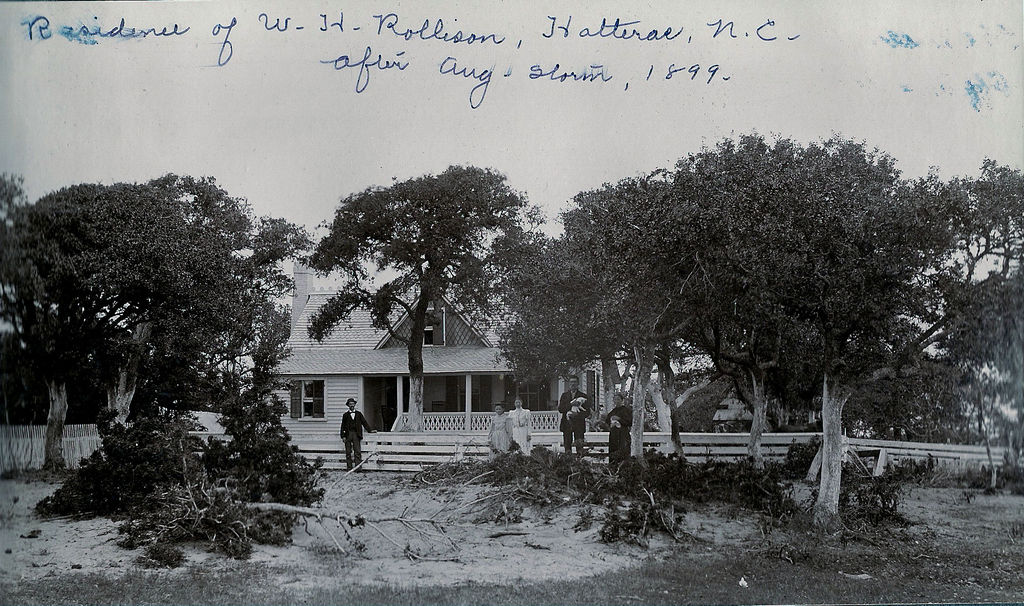

Hatteras Island was devastated by the August hurricane of ’99. The Weather Bureau station in Hatteras Village was hard hit, as the entire southern end of the Outer Banks fell within the powerful right-front quadrant of the storm. Winds at the station were clocked at sustained speeds of over 100 mph, and gust were measured at between 120 and 140 mph. Ultimately, the station’s anemometer was blown away, and no record was made of the storm’s highest winds. The barometric pressure was reported as “near twenty-six inches” (880 mb), which, if accurate, would suggest that the San Ciriaco Hurricane may have reached category 5 intensity. Though that’s not likely, it’s understood that this hurricane ranks as one of the most powerful ever seen on the Outer Banks.

One of the most chilling accounts of the storm was a report filed with the Weather Bureau office in Washington, D.C., by S. L. Doshoz, the Weather Bureau observer at Cape Hatteras. The Following excerpt from his report details the extent of the storm surge and the struggle for survival endured by the residents of Hatteras Island.

— Excerpt from North Carolina’s Hurricane History by Jay Barnes, Fourth Edition

Through the Lens

Media & Publication Accounts

Newspaper Archives

A collection of archival news stories from 1899 (related section highlighted)